Submitted by Kate on

Tucked away on a small plaque along Big Bay Point Road is the story of how Innisfil contributed to the construction of a great ship, the largest of her time for almost fifty years.

Plaque located on Big Bay Point Road, west of the entrance to the Bee Happy Campground

It was named the Great Eastern, an iron sailing steam ship first conceived of by Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859). Brunel was an English mechanical and civil engineer whose ground-breaking designs and creative solutions to ongoing problems of engineering earned him the number two spot on a list of “the 100 Greatest Britons” poll conducted by the BBC in 2002. Among his achievements were the construction of numerous dockyards, bridges, and tunnels (including the Thames tunnel, still in use today by the London Underground), the Great Western Railway from London to Bristol and on to Cornwall, and even the design and construction of a temporary pre-fabricated hospital that could be shipped overseas for use during the Crimean War. This building, known as Renkioi Hospital, incorporated various necessities of hygiene. Its design was so successful that it was said to have ten times fewer deaths than the hospital it replaced, earning praise from the famed nurse Florence Nightingale.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel in 1857

Not least of his contributions to engineering, however, were three significant steamships: the Great Western, the Great Britain, and finally, the Great Eastern. After completing the Great Western Railway, Brunel considered that service could be greatly extended if it linked with a steamship line, and so the Great Western was created in 1838. The success of the first led to the design and implementation of the Great Britain, the largest ship of her day, made with iron and featuring a screw propeller. By 1851, Brunel began to contemplate the possibility of a ship that could sail to India without refueling after proving that a larger ship could carry fuel for a disproportionately longer voyage. Thus the idea for the Great Eastern was born.

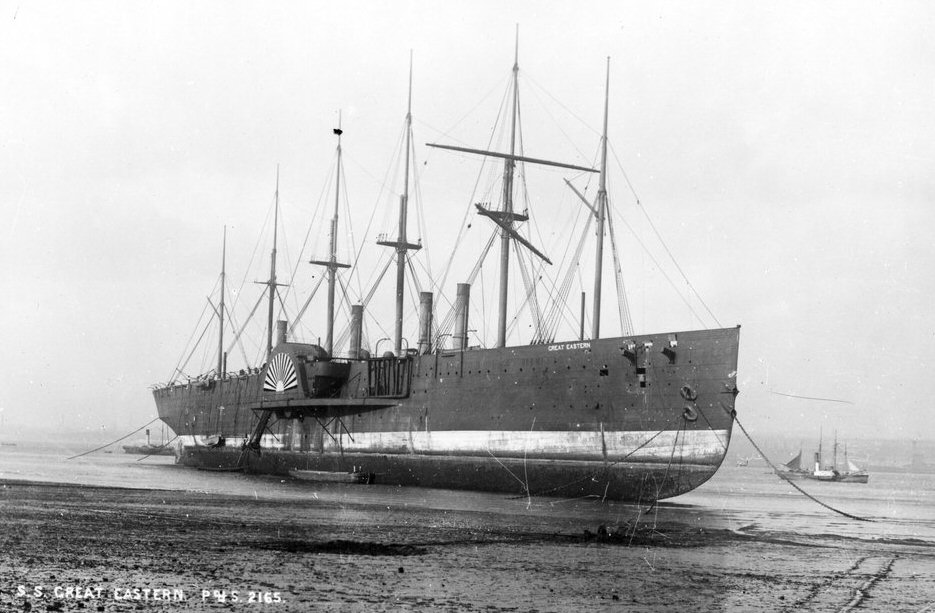

Teaming up with Scottish shipbuilder John Scott Russell and beginning construction at Millwall on the north bank of the river Thames, it was 692 feet (211 metres) long, 120 feet wide, and weighed more than 18,915 tons, making it the largest vessel ever built – six times over! Despite the increased weight, the ship was so well designed that the ratio of hull structure weight to its water displacement was less than a quarter. It featured a double hull, had both paddle and screw propulsion, and six masts to carry its sails. This, of course, is where Innisfil comes in.

The Great Eastern in New York Harbor, 1860

More than 5,600 km away from London, Thomas Webb was clearing his land located within lot 23 on the 12th concession of Innisfil. Thomas was one of nine children born to Thomas and Fanny Webb who had emigrated from Gloucestershire, England in 1842 with their family. The senior Thomas had settled on the south half of lot 15, concession 10 in what was later to be known as Stroud, while the younger Thomas and his siblings spread throughout Innisfil and Barrie in the following years. The timber on lot 23 was immediately distinctive for its size and quality. Eventually, a log that was 120 feet long and 2 feet 9 inches in diameter was felled there and required ten teams of horses to pull it to Lake Simcoe. From there, the log was shipped to England and its considerable size earned it a spot as one of the six masts on the gargantuan Great Eastern. These six masts were named for the days of the week, starting with Monday near the bow and ending with Saturday at the stern, and together they could hold 6,500 square yards of canvas sail. Since the first five masts were made of iron, we know that the log from Thomas Webb’s lot became the sixth and final mast known as Saturday. This had to be constructed of wood as it was closest to the ship’s compass, and another iron mast would have interfered with compass readings.

Thomas Webb and his wife Nancy Bowman, c. 1855

While Brunel had conceived of the ship’s name as Great Eastern, it was initially to be launched in November 1857 as Leviathan, but reverted back to Great Eastern shortly after the launch failed. It took three months to finally get the colossal ship to the water where it famously had to be launched sideways, thus beginning a spiral of bad luck. The maiden voyage was cut short when an explosion blew apart the forward deck, killing five crewmembers and injuring five others. After repairs were made, there was insufficient traffic to India and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) to warrant the eastern voyages it was intended for. Instead, the Great Eastern sailed west across the Atlantic, but its focus on providing luxury accommodation and slower speed meant it could not capitalize on the more lucrative trade of transporting emigrants. Several transatlantic voyages later and the company that owned the Great Eastern ended up £142,000 in debt, forcing them to sell the ship in 1864 for £25,000 when it was worth more than £100,000 in material alone.

From there, she was chartered to the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company where she was responsible for laying more than 48,000 km of submarine telegraph cables, including the first to connect Europe to North America in 1866. Between 1869 and 1874, the Great Eastern laid six more telegraph cables between the two continents as well as one from Aden in Yemen to Bombay in India. After this, a new attempt was made to transform the great ship into a passenger liner, which ultimately failed. She was then used primarily as a floating billboard and as a showboat with a concert hall and gymnasium, making trips between London and Scotland. In 1887, the ship was again sold where it returned to Liverpool and was slowly broken up in 1888 and 1889.

The Great Eastern beached for breaking up in Rock Ferry

Although the massive ship never quite lived up to the sizeable dreams of her visionary creator, the Great Eastern nevertheless played quite a significant role in the advancement of shipbuilding and engineering, as well as transatlantic communication. She has earned a place in the history books, and for its role in contributing the final wooden mast, Thomas Webb’s land will be remembered alongside her.